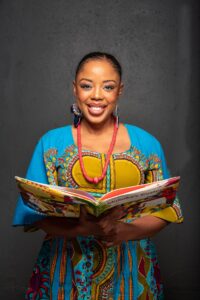

Toronto-born of Jamaican parents, Nadia L. Hohn is an award-winning author, educator, and “artivist” who advocates for diversity in children’s literature. We are proud to highlight this internationally active writer as our Day 17 honoree.

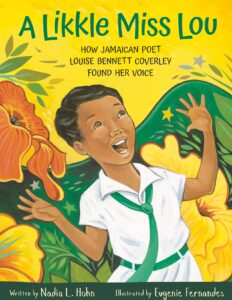

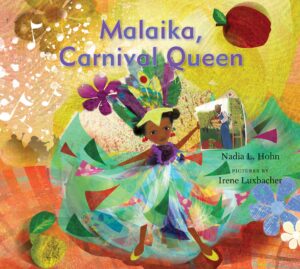

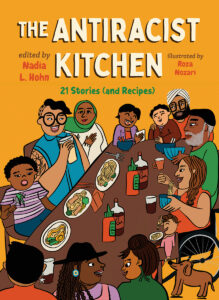

NADIA L. HOHN is the author of Malaika’s Costume (2016) which was the 2021 TD Grade One Book Giveaway, a program which distributes over 550, 000 copies to Canadian first graders. Her other books in the series are Malaika’s Winter Carnival (2017), Blue Spruce Award-nominated Malaika’s Surprise (2021), and Malaika, Carnival Queen (2023), published by Groundwood Books. Nadia has also written Harriet Tubman Freedom Fighter (Harper Collins, 2018), Music (Grade 5) and Media (Grade 6) in the Sankofa Black Heritage Collection series (Rubicon Publishing Inc, 2015), and A Likkle Miss Lou: How Jamaican Poet Louise Bennett Coverley Found Her Voice (Owlkids Books, 2019). Nadia is the editor and contributor of The Antiracist Kitchen: 21 Stories (and recipes) (Orca, 2023). She continues to write plays as well as picture books and novels for young people. Her freelancing work has been featured in anthologies and publications, like Psychology Today, Quill & Quire, Owl, Chickadee, Book News, ByBlacks, and Write.

NADIA L. HOHN is the author of Malaika’s Costume (2016) which was the 2021 TD Grade One Book Giveaway, a program which distributes over 550, 000 copies to Canadian first graders. Her other books in the series are Malaika’s Winter Carnival (2017), Blue Spruce Award-nominated Malaika’s Surprise (2021), and Malaika, Carnival Queen (2023), published by Groundwood Books. Nadia has also written Harriet Tubman Freedom Fighter (Harper Collins, 2018), Music (Grade 5) and Media (Grade 6) in the Sankofa Black Heritage Collection series (Rubicon Publishing Inc, 2015), and A Likkle Miss Lou: How Jamaican Poet Louise Bennett Coverley Found Her Voice (Owlkids Books, 2019). Nadia is the editor and contributor of The Antiracist Kitchen: 21 Stories (and recipes) (Orca, 2023). She continues to write plays as well as picture books and novels for young people. Her freelancing work has been featured in anthologies and publications, like Psychology Today, Quill & Quire, Owl, Chickadee, Book News, ByBlacks, and Write.

Nadia L. Hohn completed her Bachelor of Arts degree in Honours Psychology (B.A. Hon.) at the University of Waterloo. She completed her Bachelor (BEd) and Master of Education in Sociology and Equity Studies in Education (MEd) degrees at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto (OISE/UT). She completed a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph.

Nadia L. Hohn has made over 100 book presentations at schools, libraries, book stores, and literary festivals in Canada, the United States, United Kingdom, Trinidad, Jamaica, and United Arab Emirates. Nadia lives in Toronto where she teaches at an elementary school and post-secondary institutions. She can read, write, and speak French, as well as some Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian.

Journey to Publication

I always enjoyed writing as a child, but I didn’t realize I had the talent to make it or that it could be a career. I’ve kept a diary since I was 9. I wrote picture books, letters to newspapers and magazines, and even first chapters to two novels before I started high school. There, I wrote plays and for my school paper, as well as for my university. I did an internship at Psychology Today magazine in New York City in 1998, but when I got home I didn’t know how to make writing into a living. I also had the belief that if I made writing a job, I’d start to hate it. So in 2003, I became a teacher so I could work with children and be creative.

The Backstory

My eighth book Malaika, Carnival Queen was released on May 2 welcomed by a launch on May 6. Like all authors, I have high hopes for my book. One of these hopes, secretly, is to find an ancestor– my maternal grandfather.

Like many of my relatives and Jamaicans over generations, both of my grandfathers migrated, as young men, for work. In the 1950s for several months at a time, GH and DP did “farm work” in the United States, much like the seasonal agricultural worker program (SWAP) in Canada, where I live. Each year, they would return home to Jamaica to support their families. I grew up to know my paternal grandfather, GH, who lived to his eighties in Florida. He was able to immigrate permanently to the US through a special program after working on farms for several years. My maternal grandfather, DP, passed away while in the US in his early twenties.

The story surrounding this death has always been hazy, having changed slightly over the years, from how he died to where he spent his final hour. At the time, my mother was a toddler, without memories of him, not even a photo.

Continuing the theme of migration started in the other books of the series—Malaika’s Costume, Malaika’s Surprise, and Malaika’s Surprise— for Malaika, Carnival Queen, not only was I inspired by my grandfathers to whom the book is dedicated, I was also inspired by a dream I had. In it, I saw relatives– ones I recognized and one I didn’t.

When I awoke, I described the dream to my mother. Having parents from Jamaica, I knew the significance dreams hold, culturally speaking. After I described it to her, she told me this mystery person was my great grandmother. I found it a little creepy that I could dream of someone I hadn’t met before. From what I’ve learned about blood memory— we have connections with those who came before us at a cellular level, whether we are aware or not. And so, Malaika, Carnival Queen starts with a dream inspired by my own.

After I had written the story and sent the manuscript off to my publisher, I decided that I needed to see and understand the world that my grandfathers inhabited. I wanted to visit migrant farm workers in southern Ontario, Canada to meet them face to face and hear their stories.

After I had written the story and sent the manuscript off to my publisher, I decided that I needed to see and understand the world that my grandfathers inhabited. I wanted to visit migrant farm workers in southern Ontario, Canada to meet them face to face and hear their stories.

My journeys to the farms and the organizations that support them felt clandestine from the start. Someone I had met at a social event had worked with migrant workers and gave me a list. I made calls and the first farms turned me down but, eventually, I made some connections. At a large farm, I met Black Caribbean men who had been working there for 25+ years, and had adult children working there as well. These were the men and women who had created a culture and a new family with each other– friendships, parties, worship services, soccer games, and cars. At another location, I met Black Caribbean men, sitting in a circle, with bottles of beer and cigarettes between them, their voices and expressions low. When I asked if they wanted their children to do this work, one man chuckled stiffly and said it was slavery. I was told that their living conditions were crowded and after a long period of discomfort, a damaged sewage pipe in their quarters was finally fixed. I sensed their isolation with vast fields of ripening fruit, waiting to be picked. I visited an outreach centre and attended a gospel concert for migrant workers. I learned so much. All the while, I wondered, why was I never taught more about these predominantly Caribbean working communities whenever we learned about farms in school, especially given the pivotal roles they play in the Canadian food chain? I invited my illustrator to accompany me on another trip to visit workers, so she could have more references for our book.

These visits, my dream and the story of my grandfathers, blended with family history, manifest in Malaika, Carnival Queen. In it, Malaika navigates grief, loss, and legacy, while holding onto her Caribbean patois, family, community, and love of soca, and Carnival. She continues to adjust and embrace her life and family in Canada– lived realities that are part of us in the Caribbean diaspora, especially for me as a second generation Jamaican-Canadian as I try to revive the memories of my elders— grandfather DP and other relatives – without photos. My diasporic longing is strong.

A rare occasion is when a new detail arises, bring the picture of my grandfather into focus. Most recently, I received names and copies of photos of DP’s mother and sister, as well as the US city in which they lived until their passing.

And so my writing journey continues.

Connect with Nadia through Social Media